Recovering the Prince Symbol Files

By Dale HughesMarch 2018

Intro

Shortly after Prince's death in April 2016, there were a few articles published about the origin of his iconic symbol. The articles were mostly about earlier design concepts, influences, and the people involved. None of the articles had actual details about the design and creation process that resulted in the final symbol, the one that everyone recognizes.

Somewhere, I still had backups of the files that Martha Kurtz and I generated during its creation. If I could find and recover the files, they would fill in some interesting and missing details about how it was created.

I knew the original backups were getting old, and at some point they would become unrecoverable. Maybe already were. If I didn't try to recover the files now, I probably never would, and they'd be lost forever.

I've heard it said that at the end of life, you don't regret the things you've done, you regret the things you didn't do. I didn't want not-trying-to-recover-the-files to become one of them. As much as I wanted to succeed in recovering the files, the fear of regret was equally motivating.

What follows are basically my notes and pictures from April–May 2016 as I documented my quest to recover the files – with explanations and a few newer pictures for context.

To be clear, this post is NOT about Prince's symbol itself.

It's about HOW I searched for and recovered the files that were generated during its creation.

The results of what I recovered can be seen in my post The Making of Prince's Symbol.

What I was Trying to Recover

Within the creation process that resulted in Prince's symbol, we had generated 3D model files, files of scanned textures and drawings, paint files, and two sets of 3D animation sequence files. I wasn't sure how much of it had been backed up. I was hoping all of it.

Where to Begin

I was pretty good about making backups of our work, but the technology that we used to create and store digital media had changed a lot over the years. The hardware, software and storage media from those days were long since obsolete.

I didn't remember the exact dates when the symbol was created. I figured it was somewhere back in the early 1990s – a time when hard disks were expensive and didn't hold much data. Typically after we finished a job, we would make backups onto magnetic media. Then the original files would be deleted from the hard disk to make space for the next job. Some files, like software tools or texture maps that didn't take up too much room, were often just left on the disk so we could re-use them on other jobs. Some of those files would continually migrate to newer/larger disks as we upgraded.

But I had not seen the Prince files for a long time. So I was pretty sure they hadn't migrated to any of my current hard disks. I had a pretty good idea where the original backups were, and I thought the chances of recovering files from them was slim at best. My hopes were that I had made copies onto something newer, but didn't know if I actually had, or where those would be.

I thought my current machine might have some clues, so that's where I began.

The Search for Clues

I work mainly on Macs these days. I searched my Mac disk and found 4 still frames from the animation with the post processing streak effects already composited onto them.

The files were in a directory of images for print/promo purposes that I had gathered many years earlier.

zoomstrk.0010.pdf, zoomstrk.0060.pdf, zoomstrk.0080.pdf, zoomstrk.0090.pdf.

The files were .pdf which meant they had been converted from some other format because I was sure we were not using pdfs back in the early '90s. So I started pulling old firewire and USB disks from my shelf to search for more. I couldn't connect the firewire disks to my current Mac, so I pulled an older Mac out of storage and connected them one at a time to that.

I searched each disk and on one of them I found an entire animation sequence. One hundred and eighty single image frames in .sgi format:

zoomstrk.0001.sgi

zoomstrk.0002.sgi

zoomstrk.0003.sgi

......

zoomstrk.0178.sgi

zoomstrk.0179.sgi

zoomstrk.0180.sgi

But they were just copies. The dates on them were not from the right era. The original animation, models, paint and scan files were not with them.

It's relatively easy to connect firewire and USB disks to a Mac and search them. It didn't take long to figure out that none of these disks had the original production files.

The Search for Archived Copies

Over the years, the media we used for archiving included micro floppies, 60Meg and 150Meg data cartridge tapes, DAT tapes, R/W CDs and DVDs, 100M Iomega Zip disks, and 1Gig Jaz disks. The timeframe for some of these overlapped and the choice of which to use depended on how much data needed to be backed up and which machine was being backed up.

CDs and DVDs would be relatively easy to check, so I started going through the hundred plus that were on my shelf. Some were labeled well and didn't need to be loaded. The ones I was not sure of I loaded on my Mac to view. There were archives of a lot of other jobs but not what I was looking for. The dates on these backups were too new. Okay, so CDs or DVDs were no help.

Next, I dug through a box with DAT tapes, ZIP disks, and a couple 1Gig Jaz disks. I looked at the label on every item in the box but found nothing with Prince on it, and again the dates seemed too new.

If there were no backups on any of those, then it meant

the only backups I had were the original backups on data cartridge tapes –

the oldest archive media I had that could hold an animation sequence.

Oh man... this was not going to be easy.

The Search for the Original Backup Tapes

At this point I'm kicking myself because I had been cleaning out closets the year before and had thrown all the older backups into large plastic tubs and dragged them outside to recycle or dispose of.

Purging is something I rarely do. As a general rule, I'm not real big on getting rid of stuff. When I do, I usually regret it later. So, as luck would have it, the tapes never did make it to recycling. I just couldn't bring myself to dispose of them. Too many years of work on those tapes.

I have an old wooden barn. You can't see the back side of it from the house. This makes 'behind the barn' a good place to hide stuff when you're tidying up before a party. Stuff like, oh I don't know... old tubs of backups tapes. So I went out behind the barn where the tubs had been stashed for over a year. The tops of the tubs were pretty weathered and one was cracked. I peeked into a couple of them. Yup, old backups and software on tapes, CDs, and micro floppies. I grabbed a 2-wheel dolly out of the barn and wheeled the tubs into my garage. I sat down on my old leather couch with the tubs in front of me and dug in.

The Tubs

The first tub that I opened was full of data tape cartridges and ants. I checked the label on every thing in the tub but found nothing of interest. I removed as many ants as I could and returned the tapes to the tub.

The second tub had gotten some moisture inside. It had more old cartridge tapes, CDs, lots of micro floppies, and mold. Once again, I checked every single item in the tub but found no reference to a Prince backup. Found some interesting other stuff though. Lots of old software that we'd used back then.

The third tub seemed the cleanest and it was dry inside. No ants, no mold. Just lots of data tape cartridges. I carefully checked the label on every tape as I worked my way down into the tub. Many of the tapes contained multiple job backups. This was common because I didn't want to waste space, so I would gang up multiple jobs on one tape. It was possible that what I was looking for wasn't properly labeled.

As I got to the bottom of the last tub, I found two Sony 150M QD6150 data cartridge tapes. The first included an item named 'prinlogo'; the second was labeled 'ARCHIVE prince, prince2'. Excellent!

There's a saying that you always find what you're looking for in the last place you look. The reason being that once you find it you stop looking. But if I hadn't found these here, I would have been out of places to look. But at least I had something.

So Now What?

So now I had these two tapes, which was great but... were they still readable? I had no idea. They were nearly 1/4 century old and had been outside through some pretty extreme Minnesota weather. Won't know until I try.

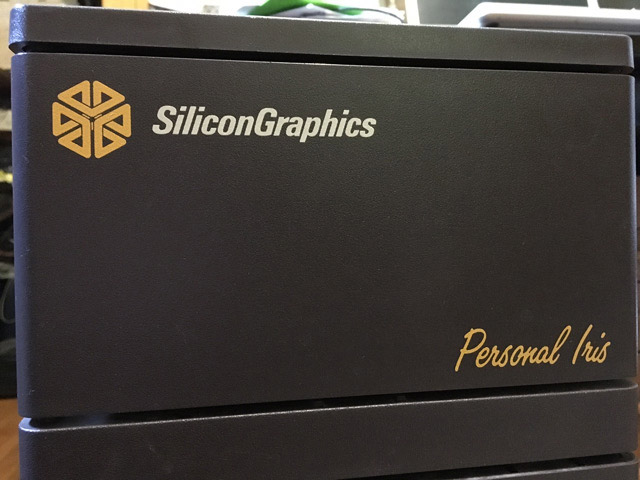

The only machines on which I created those kind of backups were Silicon Graphics (SGI) machines. I had an SGI 3130 way back when, but that seemed too old, and I was pretty sure it did not write 6150 tapes. That meant they were most likely created on an SGI Personal Iris. We were using two of them around that time. I had a Personal Iris 4D25 and Martha had a Personal Iris 4D20.

Hmmmm... Can I get one of those running? I still had the SGI boxes but I'd have to find a monitor that worked with those.

The graphic display monitors we used on these machines were bulky 19" Cathode Ray Tubes (CRTs). Over the years I had accumulated a large number of CRTs but storing all those big clunky things was getting to be a problem. Sadly, we had recycled almost all our CRTs a few years earlier. So, I no longer had one that worked on the Personal Iris.

Time to call my old friend and colleague Scott Gaff. I told him I was thinking of getting a Personal Iris running and asked him if he had a monitor that would work on it. No, he didn't. We both still had monitors for an SGI Indy but they used a different type of connector. To connect one of those to an Iris you needed a special cable. I thought I might have one of those cables but wasn't sure.

But, the Personal Iris also had RS232 serial ports and we both had a Wyse terminal. These are CRT monitors with a detached keyboard, but they only know how to display text. They're often referred to as dumb terminals. Mine is a WY-75 with green phosphor and displays 24 rows of 80 characters. So if I couldn't find the right graphics monitor or the special cable, I could resort to running the Iris headless with just the Wyse terminal connected to a serial port.

I dug through my old cables looking for the cable that could connect the Indy monitor to the Personal Iris but couldn't find it. Looked like the Wyse terminal was my only option.

Can I do this...?

What would it take to get a Personal Iris up and running? I didn't want to try unless I thought it was possible.

So, what would make it not possible?

I started thinking through issues and solutions.

- The SGI will have to power up.

– Well, I have two of these machines, one of them should power up. - It has to boot up IRIX (SGI's version of Unix).

– Without a graphics monitor it'll be hard to tell if it has. But again, I have two; one should boot. - I'll have to physically connect the serial port on the SGI to the Wyse terminal.

– I should have all the connectors and cables in the closet somewhere. - I'll have to configure the Wyse terminal to the same settings that the Iris was last configured to.

– I can keep guessing at these until it works. The Wyse is relatively easy to change in the setup menu.

– Oh, but wait... Did I leave a getty enabled in IRIX? ('getty' is the process that, if enabled and running, issues a prompt and allows you to log in through the serial port.)

– If no getty is running, the serial ports will just act dead – so I won't know if I have the settings correct – which won't matter anyway because without a getty running there is no logging in through the serial port.

– I think the Personal Iris has a couple serial ports. I probably left a getty running on one of them... I hope. - If everything works and I make it this far and the Iris gives me a login prompt... I still have one big problem. I'll need to enter a valid user name and password.

– Think... Think... I remember a couple user names & passwords I used back then. One of them should work.

So, if I could get an Iris to boot up, and if I had left a getty running, and if I wired the Iris correctly to the Wyse terminal and configured that correctly, I should in theory get a login prompt. If I can remember my user name and password, I'll be able to log in and try to read a tape. If I can't log in I'm screwed.

Well, that all sounded reasonable.

Anything Else?

My biggest and probably my most valid concern was that the tapes might not be readable. Being able to read them seemed like a long shot at best, but I didn't see any other solution. I figured the game wasn't over until I either got the tapes to read, or was convinced that the tapes were unreadable.

Then I realized one more problem. Even if I got a Personal Iris running and got logged in, and I was able to read from the tapes onto the machine's local disk, that does not make the files accessible. I needed them on a modern machine where I could do something with them. Removing the old SCSII disk from the Iris and trying to mount it on something more modern did not seem like a very good option. Nor did trying to mount any modern devices to this old machine.

The only way I could transfer the files would be to get the Personal Iris onto my current ethernet network. Sure, these machines could network, but they were not exactly plug and play.

I called Scott again and we talked about SGI networking issues and how we used to connect a Personal Iris. They had a 15-pin ethernet port that connected to a heavy drop cable, which connected to a small box, which had a vampire tap into a backbone cable. You could only network machines together if they were relatively close to the backbone where a vampire box had been attached. Connecting one of these vampire boxes to the backbone was not an easy task. You needed a special tool that would cut a hole in the cable just the right size. The backbone cable had marks on it where you could mount the boxes because they had to be spaced correctly.

I still had all the networking parts. I wasn't sure what shape my backbone cable was in anymore. I had used it to run power from a fence charger in the chicken coop, across the lawn, and up to an electric fence where Ed the horse and Lightning the donkey were pastured. As I remembered, when I retired it from that service it was looking pretty fried.

But Scott and I kind of remembered having some adaptor that we used to upgrade the ethernet port so it could take a modern day RJ45 ethernet cat5 cable.

At this point I had not even mentioned to Scott why I wanted to resurrect this old machine, but he was already into it. I did eventually tell him why. Probably wouldn't have needed to though. He would have still wanted to just for the fun of it.

Up until now everything had just been thought experiments and a couple phone conversations. I hadn't actually touched any hardware yet.

April 30, 2016 – Less Talk, More Action!

I happened to have pulled my Personal Iris 4D25 out of the closet several months earlier because I needed something to elevate my vertically challenged Christmas tree. The Personal Iris was a nice solid box (steel with plastic skin) and seemed the perfect height when it was laid on its side. With a red skirt draped over it, you never knew what was under there. After the holidays the tree was taken down and tossed out, but the Personal Iris was still sitting in a corner in the living room. So I dragged it into my office and started an initial examination.

Behind that panel is the tape drive.

I opened up the side of the Personal Iris and saw rust. (Tree stand leaked?) I convinced myself that it was only surface rust and that everything else was probably fine.

The serial port issue –

SGI used a DB9 F (9-pin Female) connector for the RS232 serial port on these machines. Many other devices used the standard DB25 (25-pin) serial connectors. Either way, RS232 connections were a pain to use. You had to have the correct cable. Even if you had a cable with the right ends, that didn't mean the cable was wired to work with the types of equipment you were connecting together.

Some equipment is wired as Data Terminal Equipment (DTE) and others as Data Communication Equipment (DCE). This originated in the days when you had a terminal (DTE) and would connect it to a modem (DCE) which would call your mainframe somewhere. To connect a DCE to a DCE, or a DTE to a DTE, you needed a special Null Modem cable. Given the fact that some devices had 25 pins and some 9 pins, it got really confusing.

We used to wire up these little adaptors to turn RS232 serial ports into telco RJ11/12 connectors. You still needed to know if the device was a DTE or a DCE. But once you put the correct adaptor on the port, you could connect any two serial ports to each other with just a flat six-wire telephone cable. Apparently these adaptors are still quite commonly used today but back then... sliced bread.

I got lucky. There was a telco adaptor already on the port. Score!

The Wyse terminal had two RS232 DB25 ports on the back. One labeled Aux and one labeled Modem. I figured the Modem port would be my best chance, so I configured a telco adaptor for it and connected the Wyse to the Personal Iris with a phone cable.

The networking issue –

Another score – there was already an adaptor on the network port which turned the 15-pin connector to an RJ45 telco connector which modern network equipment uses. I connected the Iris to my router with a cat5 cable.

In theory, that should take care of the hardware issues.

The booting issue –Another issue that I fortunately remembered at the last minute – The Personal Iris did not like to boot up if it didn't have a keyboard and mouse attached. Not the serial terminal, that didn't count. It needed the keyboard and mouse that you'd use if you had a graphics monitor attached. And it had to be the correct keyboard and mouse.

I found a stack of keyboards and mice in the closet and chose the oldest looking ones – vintage putty yellow. I had some newer grey SGI keyboards, but I was pretty sure they were for later model SGIs like the Indy and O2. (Yes, I still have those too.)

The keyboard plugged into a dedicated keyboard port on the Personal Iris and the mouse plugged into the keyboard. The optical mouse had to be placed on a special (metal) mouse pad which has dots on the surface. The mouse for the Personal Iris was very specific to this machine. I had tried some in the past that looked exactly like these, but the Iris ignored them.

Cleared For Launch

I plugged the Personal Iris into the power and turned it on. Wow, this machine is loud. But that's the way I remember it, so no worries. If the getty process was running, it was probably going to allow a 9600 baud connection. It might jump through multiple baud rates in an attempt to sync but 9600 was kinda my default go-to speed. So I powered on the Wyse and brought up its configuration screen. I selected my best guess – VT100 emulation, 9600 baud, 7 data bits, one stop bit, Handshake XON/XOFF. I hit the enter key a few times – but no luck. The Wyse just sat there blinking a green cursor at me.

I tried other combinations of baud rates and settings on the Wyse and continued trying to get a login prompt from the Iris. Still no luck. I tried some other cables and adaptors. At one point I brought out my RS232 break-out-box so I could watch the signal on the specific leads. Eventually I was convinced that it was wired correctly.

I put my ear closer to the Iris and pressed the return key to see if I could hear it make a little blip of a noise like it was processing it. Then I remembered that these machines didn't always come up in multi-user mode. It may come up in single-user mode first, and prompt me at the main graphics monitor to ask if I want to enter multi-user mode. Well obviously I didn't have a graphics monitor connected, so I wouldn't know if it was prompting me for anything or if it was spitting out boot errors.

As I'm listening for a sound change, I notice a login prompt on the Wyse. Holy crap. It's up. I can try to log in.

I can remember two user names and two passwords from back then, so I try the four combinations from those two but each time the login fails. Then it stops giving me a prompt.

I don't remember these machines having any limit on the number of failures but just as I'm about to reboot, it prompts me and gives me another chance. Maybe I can log in as root. I might still remember the root password. I enter 'root' as the user name, hit enter and it logs me on without asking for a password. Whoa, I would never have used it in production that way, but apparently when I put this machine down for what I thought would have been the last time, I removed the root password in case I ever needed to bring it back to life. I'm so proud of myself for my foresight.

Getting Networked

I'm still too chicken to try reading the tapes because I'm not ready to face possible defeat yet. If I can't read the tapes, it's game over! So I move on to networking the Iris just in case.

The Iris is physically connected via the ethernet telco adaptor and cat5 cable to my router. But that didn't automatically mean they would be able to talk to each other. Modern networking equipment will dynamically assign an IP number to a device when you connect it. (Dynamic Hosting Configuration Protocol aka DHCP.) I was pretty sure the Iris didn't do DHCP. That meant I would need to configure the Iris with a static IP and get my router to recognize it.

Called Scott again. Between the two of us and a little Googling we figure out how to assign it a static IP. I log into my router using my Mac and I can see all the devices on my network. I randomly pick an IP number that is not being used. I edit the network files on the Iris and do a shutdown -g0 -p. The machine goes down and I take a breath.

I turn the Iris back on and watch the network devices read out on my router control panel. It's there. The Iris is on the network. One step closer.

I don't know how long these links will be good for but here is where I found some of the info:

software.majix.org/irix/network-setup.shtml

nekochan.net/wiki/IRIX_Installation_and_Customization

Here Goes Nothing

The First TapeI'm getting a little excited now because the moment of truth is here. Will the tapes read or are they too old or damaged? It takes a couple tries for me to remember how to insert the tape correctly and that I have to close the locking latch.

At the command line on the Wyse, I issue the read command tar -xv which on these machines defaulted to the tape drive. The system responded with tape read error:.

Damn! – this can't be happening. I've come too far.

Calm down. Don't get discouraged...

Try again. Same results. Maybe I should try a different tape. I go back to the garage and get a couple other tapes that look to be in good shape. I try them. Same result. At this point I am pretty discouraged so I power the machine down.

I Can't Quit Now!

Hmmmm... What else can I try?

Oh, I know, maybe it's the tape drive itself. Martha's 4D20 has the same type of tape drive; I could try swapping them. I pull the tape drive out of the Iris. The mechanical parts are exposed on these, so I grab the motor and try to turn it. It's stuck. I grab the belt drive attached to the motor and start working it back and forth until the motor moves freely. I install the tape drive back in the Iris and again power it up. This time it boots right up and give me a login prompt, so I log in.

I put the Prince tape back in the tape drive and again issue tar -xv. A loud whining noise comes from the tape drive as it comes to life. On my Wyse terminal I start to see the files being read. The first files coming off were for a different job. I just had to watch and wait.

At this point I'm getting giddy.

I have to give a shout-out to Sony for this tape. It's been 24 years since I created this backup. The tape sat in a plastic tub outside through a hot humid summer and brutally cold Minnesota winter. And here it was – doing what it was made to do.

As I watched the file names appearing in beautiful retro green on my terminal, I grabbed my phone and recorded some video.

Then the scrolling stopped and it ended in tape read error:. I could see that it stopped before the end of the effects animation sequence. Even though it didn't make it to the end, I knew I had enough. It was the same sequence that I found earlier on an old hard disk, but these would have the original dates. Plus I got the animation sequence without effects and some key texture files that I hadn't found anywhere else.

I checked (df -k) to see how much room there was on the disk. Not much. I will need to transfer the files to my Mac then delete them from the SGI's disk so I can read the next tape. I bundle them up into a .tar file so the dates will be preserved, then launch ftp (File Transfer Protocol) on my mac.

I use ftp to transfer the new .tar file from the SGI to my Mac. (Fortunately ftp was still compatible between the two systems.) On my Mac I un-tar (tar -xv) the file and look at the dates. April 21 and 22, 1992. Cool. These are the originals.

On my Mac, I make a backup of the .tar file onto a thumb drive/memory stick. I don't want to delete the files from the SGI, but there won't be room to read the second tape if I don't. I assure myself that there are copies of these files now on two other devices, but I still cringe as I delete the files from the SGI.

The Second TapeI insert the second 6150 tape and issue the command tar -xv. Again the Wyse's green screen fills with rows of characters. The tape reads perfectly all the way to the end. (Another shout-out to Sony.)

The files from the second tape are our working directory where the geometry was built and the effects software scripts were run. The dates on these files, however, are not the original dates. The working directory was originally on Martha's 4D20. The files in the working directory are relatively small so there was no rush to remove them. When I eventually backed them up, they were copied to the 4D25 where I was doing backups, but the original dates were not preserved. So all the files on this tape acquired the date Mar 14, 1994 – the day I copied them. The reason they were copied to the 4D25 to be backed up was so that I could gang them up with a couple other jobs so I didn't waste space on the tape.

This could mean that the original files from the work directory (with the correct dates) are still on a disk in Martha's 4D20.

I again make a new .tar file of the files from the second tape and transfer it to my Mac. When I'm sure I have the files safe and secure, I power down the SGI and thank it for its many wonderful years of service.

Everything up to this point happened relatively quickly – only a few days. Now comes the task of figuring out what I have. The problem here is that many of the files are in formats no longer used. Some are Unix ascii scripts which I can still easily read. But the 3D rendering was done in NeoVisuals, which produced .GEN image files. There are no converters for those. The models are a mixture of NeoVisuals binary files and ascii files with vertex lists and lighting info. There are also .sgi files, which are raster image files.

So now I have the files safely on my Mac, but I can't view any of them.

Converting and Viewing Obsolete File Formats

In order to view the obsolete .GEN image format, I resurrected and updated some of my old C code and re-complied it on a MacBook Pro. It turns out that the byte order on the SGI is different than on the mac (that was a pain), and the gcc compiler is much fussier. It took a while just to get my tools that read .GEN files to compile. So I took a shortcut and used them to make a little program that would read the .GEN files and dump them out to a raw rgba file. I had to make note of the resolution (xres x yres) of the scan lines, but was then able to run them through ImageMagick to convert to .jpg so I could view them in a browser.

To display the original geometry/model files, I converted them to Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) elements, which also display in browsers. Some of the models were converted to a vector format to view in a 3D webGL viewer.

Figuring Out What I Had

My notes on converting the files and figuring out what I had are quite lengthy. I am not including them here as the investigation process was very detailed. I had to be sure that what I was piecing together was accurate. To do that, I had to figure out the order in which the elements were created, why each element was created, what software was used, and in some cases what piece of equipment, scanner, or camera was used to create a file.

For example, I figured out that the files from the video camera that we used to scan art work and texture maps have a 1/2 scan line on the bottom that is green, the far right has a blue tinted vertical line, and the far left has a whitish line. This was just one of many clues that helped me deconstruct composite images to see where the elements came from and in some cases the order in which they were composited.

In the case of the 3D elements, I needed to figure out the coordinate system that NeoVisuals used so I could replicate the placement of models and cameras.

Converting the files and setting them up for viewing took me a couple weeks. As I was figuring out what I had, I began to realize what I didn't have.

What I Didn't Have

One of our working directories was missing. The one that contained some key image files of flat artwork and sketches that had been scanned, cropped, and matted/painted. Only the final files from that directory had been copied over to the directories that I recovered from the tapes. There was a remote possibility that these (along with the originals from tape 2) were still on one of the 4D20's hard disks. If they were not there, then it was also possible they were on an old Mac IIfx which we had networked into our system back then. I dug through my closet but could not find the Mac IIfx – may have dropped that off at recycling when I took the monitors in.

May 9

Wanted to search for backup files from the Mac IIfx which are on Zip disks, but my Zip drive was a SCSII so I couldn't connect it to my current Mac. Found a USB Zip drive on Craigslist. Drove to St Paul and picked it up. At home I connected it to my Mac and searched through all the Zip backups from the Mac IIfx. Didn't find any image files or paint files transferred to Zip disks from back in 92–94.

May 11

It's bugging me that I don't have the original dates on the second tape. I have a pretty good idea what disk I copied them from before making the backups, based on some of the scripts that are on the second tape. The Personal Iris has two disk bays; a small one in the top just above the tape drive, and a larger one closer to the middle of the machine. The system disk was typically in the small bay and a larger capacity disk for work files was in the lower bay.

So I open the lower bay of the 4D20 where the work disk should be mounted... and it's missing. The machine only has its system disk. The work disk, wherever it is, may still have the original files with the original dates – if I didn't delete them after backing it up. I may have taken that disk out to mount it in an external box with another disk when I migrated to an SGI Indy or O2. It would be great to find the original file dates so I could put together a timeline to see the whole thing go down. It happened pretty fast.

May 13

Aside from finding the original files from the second tape, I also wanted to find the missing scan/paint files. When logging in to the Iris, the default home directory is /usr/local/people/[USERNAME], which is on the system disk. It's possible that one of us had done some work in our home directory.

Tried to fire up the Personal Iris 4D20 (bear) to see what was on the system disk. Could not get a login prompt on the Wyse. While looking at the back I noticed that the video output also included an SVGA port. Why hadn't I noticed that before? Argh. Well, I have a Sony TV sitting on my dining room table (in transit to another room) and it has an SVGA port, so I hooked it up and powered them both on.

The machine starts booting but gets stuck doing its files system check (fsck). It gives me options for fixing the file system, which I do. It takes a couple tries/reboots but finally makes it through the fsck, then complains about not having a network cable connected. It eventually accepts the fact that I'm not hooking up a network cable, boots up and gives me a login screen. The keyboard I was trying to use didn't work though. I swapped keyboards with my other Iris and it sort of worked – the keys worked intermittently. Was able to log in using one of the username/password combinations that I remembered from back then. Did not find any files of interest on the system disk.

I can see which disks were mounted locally (efs) and which were mounted across the network (nfs). There are lots of commented out lines showing that some of the disks moved from one Iris to the other and some were moved to a couple SGI Indys ('turtle' and 'owl') when they were added. (Disk 'bull' was moved to 'owl', and disk 'g' had been on 'bear' and 'grin2' at different times.)

I grab an external disk from the closet. It's in a box with the SCSII address set to 4. Based on the fstab it should try to mount. I power down the Iris, connect the disk and boot back up. The disk would not mount. It made a lot of noises trying but continued to fail. Ok, giving up on that one.

Hooked up another disk box which has two disks in it. The fstab had an active entry for dks0d4s7 so it went ahead and mounted SCSII 4. It had newer stuff but no Prince files. The second disk in the box was set to SCSII 6, so I edited the fstab to activate the commented-out entry for dks0d6s7. It mounted the second disk fine but the only thing on it was a World Figure Skating Tour backup from 1999. Ok, nothing of interest there.

May 17

Found the Mac IIfx in the barn.

Also found an older system disk from the 4D20 in the closet. This one was probably replaced when a newer operating system was released and this disk wasn't big enough.

May 18

The older system disk from the 4D20 had a piece of tape on it that said it was from a machine named 'still1' (Stillife and Kicking #1) and that it has the vfr (video framer) on it. The hardware for the vfr is still in the 4D20 which is the only machine the hardware was ever in. So I knew the 4D20 had been renamed. It also showed that it was pulled out in 1995, so it could possibly have the missing scan/paint directory on it.

I installed the disk and turned on the power... CRACK... smell of burnt electronics. Waited... system never came up. Shut it down. Maybe I can get the disk fixed. I contacted a local company that did data recovery from old disks but the cost was beyond what I was willing to spend since I didn't know if I would find anything.

And that's where the search ended. I still have a few more SGI disks to check, and could have attempted to resurrect the Mac IIfx. But I needed a break. I have not made any more attempts to locate the missing scan/paint directory since May of 2016. But that doesn't mean that I won't. Not sure if I could handle the regret of not trying.

If you want more detail on anything mentioned above or just want to comment, drop me a note.

–Dale